This article appeared in The Psychiatric Times on Oct. 28, 2011. Treating Mental Illness Before it Strikes details the efforts of the psychiatric community throughout the twentieth century and the beginnings of this century to identify and treat young adults before they become psychotic. Most recently we have heard about the debate on the proposed insertion of a new category of disorder —psychosis risk syndrome — into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM V), and of Dr. Allan Frances’s outspoken views on this subject. Some of us have also read about the proposed McGorry medical trial in Australia, which was heavily critized on ethical grounds because the trial involved putting youth as young as age 15 (most of whom would never go on to develop psychosis) on antipsychotics if there was evidence of a family background of psychosis.

In June 2011, a number of Australian newspapers reported that a high-profile medical trial targeting psychosis in young adults would not go ahead. It was to be conducted by Prof. Patrick McGorry, who had been Australian of the year (an honorary and mostly symbolic title bestowed by the Australian government on an unusually deserving citizen advocating worthy causes). In the proposed trial, youths as young as age 15 would receive Seroquel (quetapine) when they were first diagnosed, not with psychosis but with attenuated psychosis syndrome (previously called psychosis risk syndrome). Treating young adults with this syndrome would nip the danger in the bud—their potential psychosis would be treated before it even arose. The trial was to have been sponsored by the drug’s manufacturer, AstraZenaca, which, like many pharmaceutical companies, was probably eager to test its medication on a younger age group to expand the market for its medications. What could be wrong with such a commendable initiative?

The final paragraph of the article reveals that

Dr McGorry has introduced a slight modification to his study, which will now go ahead. Instead of Seroquel, he will now test the efficacy of fish oil.

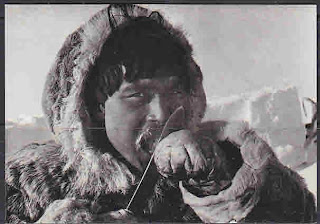

Slight modification? This is huge! To favor conducting a medical trial with fish oil rather than with Quetiapine (Seroquel) is astonishing, not least because the drug manufacturer is now out of the picture. Fish oil is becoming popular for its purported benefits in preventing schizophrenia (and depression). Will fish oil be found to do all that its proponents claim it does or will it be found to be ineffective in preventing psychosis? Wouldn’t a rather simple solution be to study the prevalence of schizophrenia in Inuit populations where the diet is high in fish oil? Studies show that rates of schizophrenia are pretty much the same (about 1%) in any culture in any part of the world, with some anomalies due to e.g. migration of certain populations. Will this new McGorry trial be properly executed? I have read that, as with niacin and vitamin C, the effectiveness depends on a dosing amount many times in excess of what is considered daily recommended intake.

Read more on the McGorry controversy here.

|

| Inuit eating frozen fish |